Is Trump’s ‘big beautiful bill’ good for US consumers?

Is Trump’s ‘big beautiful bill’ good for US consumers?

The bond market is sending Washington an unmistakable message: The U.S. budget deficit is a problem we can no longer ignore. Yet, the GOP budget bill seems to do precisely that.

If the ballooning debt persists, long-term interest rates will stay elevated and could continue to rise. While politicians celebrate tax cuts, bond investors, the people and institutions lending money to the U.S. government, are far less enthusiastic. They’re demanding higher returns to make U.S. debt attractive: The 30-year Treasury yield briefly surged past 5% in May.

This milestone hasn’t been reached since 2007, with the exception of a quick spike in 2023, when high inflation sent the entire yield curve higher (the 10-year yield also breached 5% during that period). With the 10-year yield hovering around 4.4% today, the spread between the 30-year yield and 10-year yield is near 0.5%—much higher than it was in 2023—implying the market is pricing in significant risks for the very long term.

Range says these aren’t just fleeting worries; they reflect deep-seated concerns about long-term inflation risks, fiscal sustainability, and the future value of long-dated dollar assets.

Why credit markets matter more than you think

We’ve always believed credit markets can be a more reliable economic indicator than equity markets. During the tariff uncertainty earlier this year, credit spreads barely widened while equity markets gyrated wildly. The credit markets called it right when they didn’t overreact to tariffs, unlike equities. They remained stable in a time when other market indicators did not.

But now those same credit markets that rarely overreact are flashing warning signals about something far more fundamental: our deficit spending.

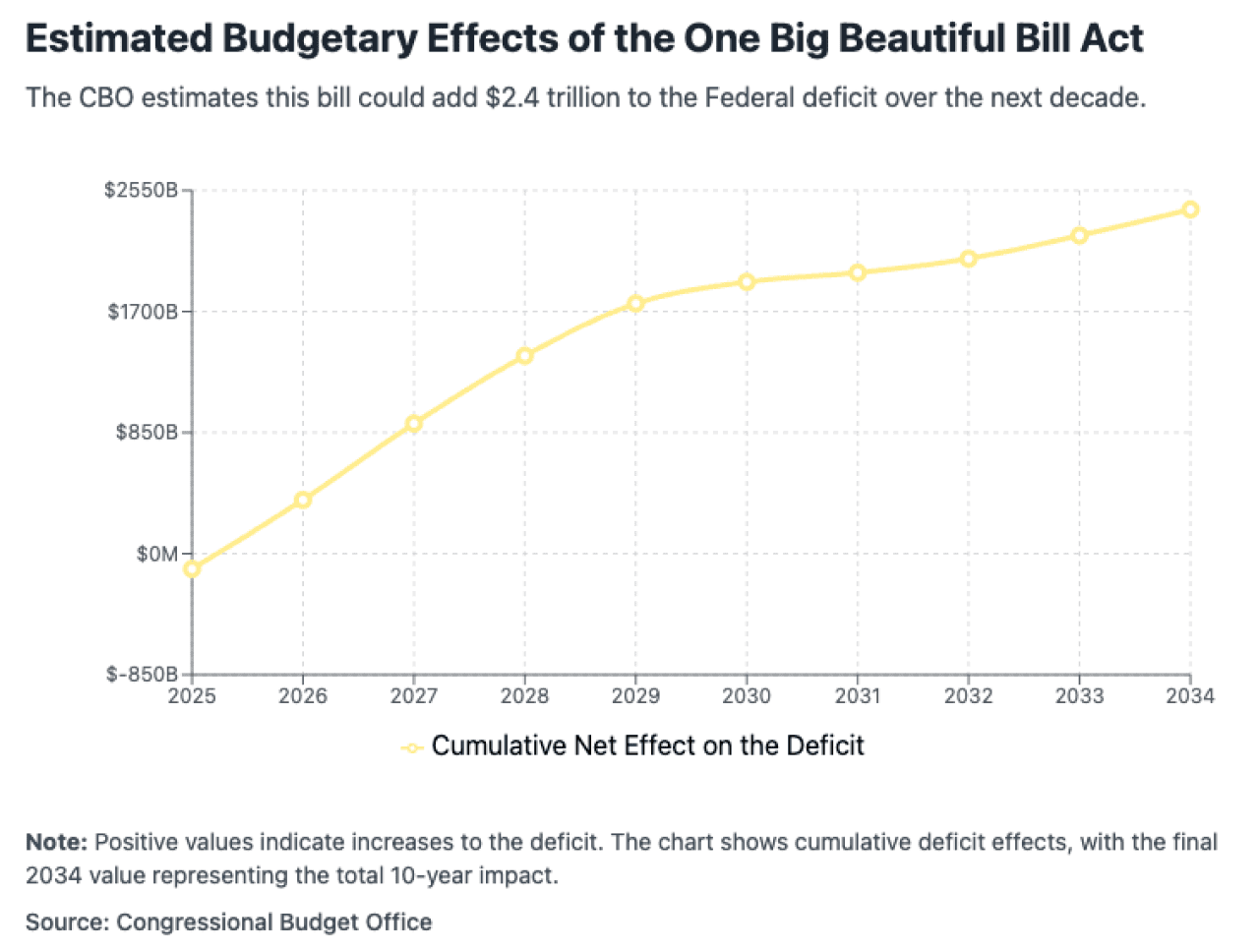

The new budget bill includes several pieces of popular legislation, such as extending tax cuts, eliminating taxes on tips, and pre-funded tax-advantaged savings accounts for newborns. But this bill in its current form is also projected to add $2.4 trillion to the national debt over the next decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Range

The response from bond investors has been unforgiving, reflected in rising long-term interest rates: 30-year yields were up 18 basis points in May, more than 22 times the average monthly change over the past year.

The real cost: Higher interest rates

Here’s what this means for actual Americans trying to buy homes or fund their businesses:

Mortgage rates are climbing: The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate hovered close to 7% in May, peaking at 7.02% on May 27, up from 6.62% in mid-April. Anyone waiting for rates to come down is facing an uncomfortable reality—deficit concerns are keeping them elevated.

Corporate borrowing gets expensive: When the government needs to issue more debt to fund spending, it crowds out private borrowers. As debt becomes more expensive thanks to an oversupply from the government, companies find it harder and more expensive to access capital, which slows hiring and economic growth.

The Fed can’t save you: The Federal Reserve controls short-term rates, but long-term rates are set by market forces. Even if anticipated Fed rate cuts materialize in the second half of 2025, the combination of the tax bill and uncertainty “sets the stage for a higher term premium,“ according to the Institute of International Finance. This means rates on mortgages, auto loans and student debt, may stay elevated even as the Fed cuts.

The debt spiral nobody wants to talk about

Let’s walk through the mechanics of how this gets ugly:

When deficit spending rises (the government spends more than it makes), the Treasury must issue more debt to fund operations. More supply of bonds means investors demand higher interest rates (yields) to absorb all that debt. Higher yields make the debt more expensive to service, which requires … more borrowing to pay the interest.

Eventually, this forces painful choices: Either slash spending (austerity that nobody wants, similar to what countries like Greece and Italy went through after the Great Financial Crisis), or have the Fed step in to buy bonds with printed money. That second option leads to currency debasement and persistent inflation—exactly what we saw in the 1970s, dubbed “The Lost Decade” for U.S. markets.

Back then, Fed Chair Arthur Burns caved to political pressure from Nixon to lower rates despite rising deficits and increasing inflation. The result? A lost decade where equity markets went nowhere, the dollar was significantly devalued, inflation spiraled out of control, and American consumers watched their purchasing power erode year after year. What made it particularly brutal was that people couldn’t escape through traditional investments—stocks were flat, bonds got crushed by rising rates, and cash lost value to inflation.

While today’s robust economy and the Fed’s strengthened independence distinguish our current situation from the 1970s, that era serves as a stark reminder of how deep economic damage can run when policymakers chase short-term political gains at the expense of lasting economic stability.

Our debt challenge is serious but fixable—if we act now

Our debt-to-GDP ratio would hit nearly 200% by 2055 if current tax provisions are extended, up from today’s ratio of about 120%, according to the Yale Budget Lab. To put that in perspective, only Sudan and Japan currently have debt burdens that high.

National debt interest payments made up the second largest spending category in the past fiscal year’s Federal Budget: That’s a 13% slice of the $6.9 trillion budget, with only Social Security costing more. That’s right—we spent more on debt interest than on our entire Defense or Medicare budgets.

Given this administration has talked explicitly about lowering long-term rates, there’s hope these red flags will prompt policymakers to come together and address the rising deficit. We’ve done this before. In the 1990s, policymakers on both sides of the aisle worked to cut spending, strategically increase tax revenues, and implement pro-growth policies to address growing deficit concerns. The result: By FY1998, the U.S. budget was in surplus for the first time since 1969, and surpluses continued through fiscal year 2001.

This tax bill, as currently written, is not a step in the right direction—while it does cut some Medicaid and food stamp spending, the potential revenue losses from its tax cuts far outweigh these savings.

Now is the time for policymakers to take the deficit seriously. We’re not in crisis yet—the economy is still healthy, unemployment is low, and that gives us agency: While it’s always hard to cut back on spending, it becomes much more painful to do it when the economy is hurting. Acting now, from a position of strength, gives us the flexibility to make thoughtful changes rather than being forced into drastic measures later.

Real deficit reduction would require the kind of politically toxic medicine that Washington has avoided for decades: fewer tax breaks, lower spending on widely used programs, or both. It’s a long, uncomfortable process that involves telling voters hard truths about fiscal reality rather than promising easy wins.

What should investors do?

This environment makes diversification crucial. Not all markets face the same pressures:

International exposure makes sense: Interest rates and deficits aren’t rising everywhere at the same rate as we’re seeing domestically. Having exposure to other markets can provide a hedge against U.S.-specific fiscal risks.

Equities still have a role: The S&P 500 is a nominal asset that can perform well during inflationary periods. People get scared when they see equity markets react to hot inflation data, but over longer horizons, equities can serve as an inflation hedge.

Short-term bonds look attractive: If you can stay short on duration—meaning bonds that mature in a few years rather than decades—you could earn attractive yields much higher than averages we’ve seen in almost two decades. If long-term interest rates continue to go up, the price of short-term bonds won’t fluctuate as much, so your principal will face less risk of losing value.

The bottom line

Tax cuts might sound appealing, but 7% mortgage rates and elevated corporate borrowing costs aren’t. The credit markets are essentially telling Congress: Do better on deficit reduction, or consumers will pay the price through higher long-term interest rates.

This isn’t about politics—it’s about mathematics. The bond market doesn’t care about party affiliation; it cares about sustainable fiscal policy. Right now, the numbers don’t add up, and interest rates reflect that reality.

For investors and consumers, the message is clear: Prepare for a higher-rate environment that may persist longer than many expect. The easy money era is over, and fiscal discipline matters more than ever.

This story was produced by Range and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.

![]()