Sanctions' failure drives de-dollarization and Russia's advanced evasion network

Natali Skripnikova // Shutterstock

OANDA examines how Western sanctions against Russia failed to achieve total economic collapse, instead creating a permanent geopolitical financial split, accelerating global de-dollarization, and forcing the rise of an advanced, state-backed evasion network that leverages models from Iran and North Korea.

- Sanctions have proved somewhat ineffective in causing a total economic collapse in Russia, but instead accelerated a permanent split in the global financial system.

- The risk of financial cutoff is rapidly driving emerging economies toward the Chinese yuan (RMB) and alternatives, leading to the de-dollarization narrative.

- Russia is implementing advanced evasion tactics, combining Iran’s oil shipping methods with North Korea’s sophisticated digital finance and cybercrime strategies.

- The continuous “weaponization of the dollar” for short-term political gains erodes the dollar’s long-term global trust, reliability, and dominance.

The international campaign of economic sanctions deployed by the U.S. and other countries against Russia following its 2022 invasion of Ukraine was a more impactful use of financial pressure than ever before, according to a 2022 International Monetary Fund analysis. While this huge number of trade and banking rules initially shocked Russia’s economy and blocked its access to the world, it ultimately did not cause a total economic failure. Instead, these sanctions have caused a fundamental and likely permanent split in how the world’s money systems work.

The main takeaway is that using financial punishment has sped up the creation of a new, independent economy led by the strong partnership between China and Russia and the growing BRICS+ group of nations. Russia’s economy has survived by focusing heavily on military and social spending, essentially creating a “war economy.” They have also been highly successful at getting around the sanctions, especially by using “parallel imports” (unofficial trade) through intermediary countries like China, Turkey, and Kazakhstan. The most important result is the rapid shift away from the U.S. dollar (USD): Nearly 90% of trade between Russia and China is now done using their own currencies (the yuan and the ruble). This shift, driven by sanctions and helped by cheaper Chinese financing, has significantly boosted the use of the Chinese yuan (RMB) in international trade.

This trend doesn’t mean the U.S. dollar will collapse immediately, but it is changing from a universal, trusted currency into one seen as having a high risk of sanctions in a new, split financial world. The core danger for the U.S. is that by using financial pressure for short-term political goals, it is eroding the trust, reliability, and neutrality that make the dollar dominant. This loss of trust risks permanently decreasing the U.S.’ long-term financial power against its biggest rivals.

The architecture of financial coercion: Goals, mechanisms, and systemic shocks

The economic actions taken by major Western powers (the G7, EU, and allies) had three main goals: to drastically reduce the money Russia made from selling oil and gas, to cripple Russia’s ability to wage war, and to cause severe damage to the Russian economy.

The three largest Russian oil companies that have been targeted by major sanctions, specifically by the U.S. and U.K., are Rosneft, Lukoil, and Gazprom Neft.

- Gazprom (state-owned): $112.2 billion (revenue)

- Lukoil: $93.84 billion (revenue)

- Rosneft (state-owned): $86.21 billion (revenue)

Key details on sanctions

Rosneft and Lukoil are Russia’s two largest oil companies and were sanctioned by the U.S. and U.K. in October 2025, which caused significant volatility in the oil market.

Gazprom Neft (the oil arm of state-owned gas giant Gazprom) was included in earlier sanction packages by the EU and U.S., and is considered one of Russia’s largest oil firms.

Initially, they used powerful financial tools, such as banning major Russian banks from the SWIFT global messaging system and freezing the assets of Russia’s Central Bank. They also stopped Russia from buying high-tech equipment needed for military production. These restrictions keep growing, shown by the EU’s adoption of its 19th package, which now includes a ban on Russian gas imports by 2027, limits on things like crypto transactions, and stricter rules aimed at stopping Russia from using its “shadow fleet” of ships to transport goods illegally.

Assessing the initial shock and mitigation (2022-2023)

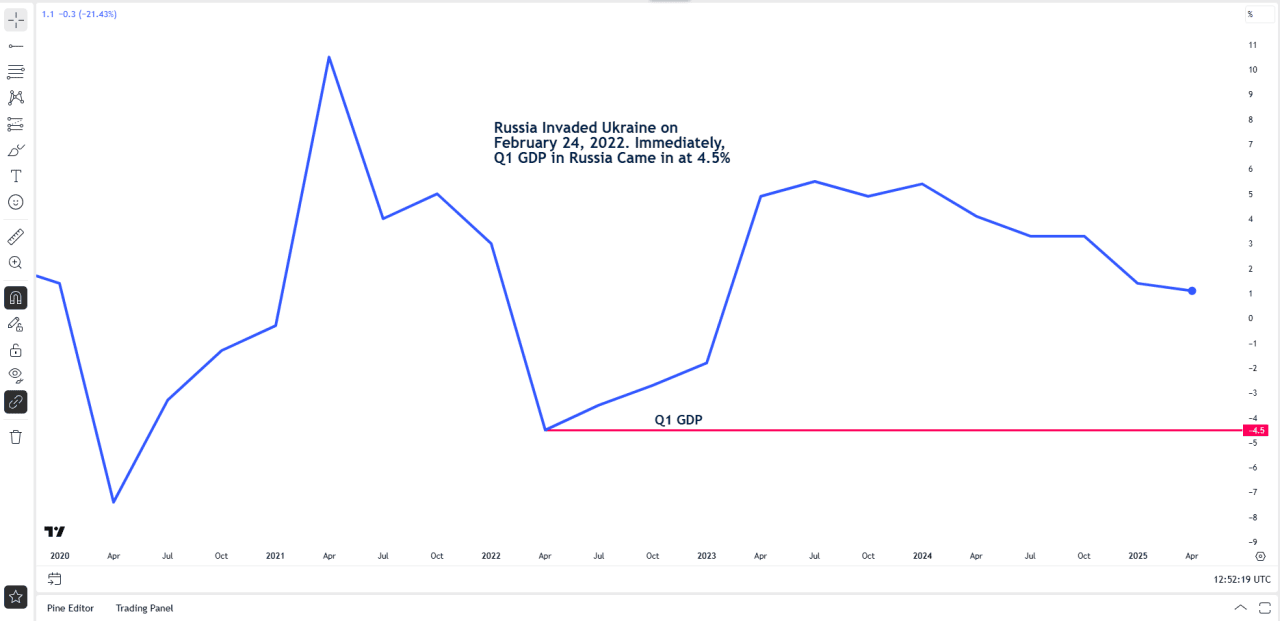

The sanctions hit Russia hard at first, severely disrupting its global trade and causing a sharp drop in people’s real incomes. Experts initially predicted a catastrophic economic collapse. However, Russia showed surprising resilience. Its economy shrank by only 4.5% in Q1 2022, before recovering to end the year with GDP shrinking about 1.8%, which was much less severe than forecasts.

Source: TradingView

This was due to two main factors: the Russian government’s strong domestic spending response (“fiscal response”), and a simultaneous surge in global energy prices. High oil and gas prices kept cash flowing into the government despite export bans, which helped stabilize its financial system and pay for replacing imported goods. Crucially, despite lower total exports and imports, Russia’s trade surplus (selling more than it buys) stayed high through mid-2024, giving the government the foreign currency it needed to pay for the military and secure vital goods through alternative sources.

The escalation to secondary sanctions and enforcement challenges

Because Russia’s economy persisted, the U.S. and EU were forced to move from simple bans (primary sanctions) to much more complicated and politically sensitive actions called secondary sanctions. These sanctions target companies and banks in other countries that are helping Russia. Recent moves include banning transactions with non-Russian payment services and, notably, sanctioning Chinese companies for buying Russian oil. This aggressive pressure on other countries is causing significant disruption, as seen by the 28% drop in Turkish exports to Russia in early 2024. This occurred because Turkish banks, fearing punishment by the U.S., began blocking payments from Russia.

Source: LSEG, Brookings Institute, IMF

The continuous need for increasingly complex and controversial measures, which now involve directly targeting strategic partners like China and Turkey, clearly shows that the initial financial sanctions are losing their effectiveness. Every time the West escalates, it increases the risk for neutral countries, directly encouraging them to find non-dollar alternatives to protect their financial independence. When a nation’s banks stop trading with another nation simply out of fear of a third country’s economic threats, it proves that relying on the threatening nation’s currency system is too risky for long-term self-protection.

Adapting to sanctions: Resilience, rerouting, and reliance on partners

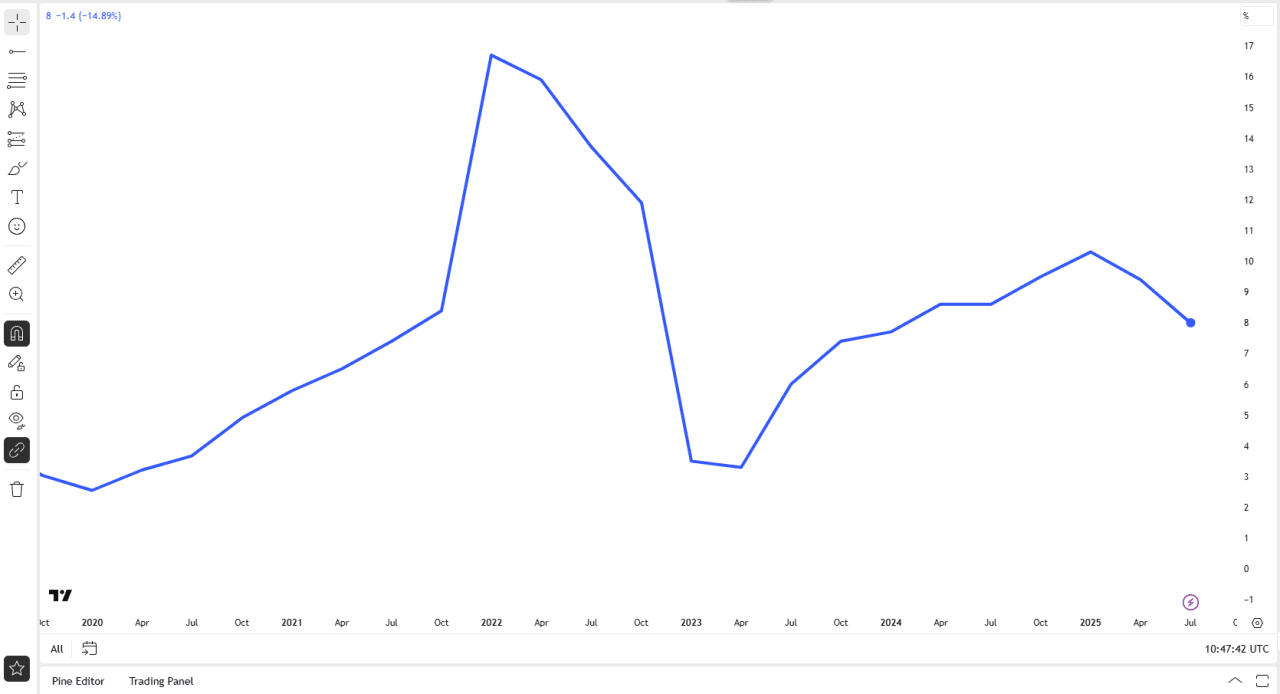

Russia’s economy in 2024 is running on two different tracks, often called a “two-speed economy.” In early 2024, the economy kept booming; moreover, the massive government spending (new highways and tax cuts) helped push it further. GDP’s up, mostly because the military buys tons, war‑time aid to folks grows, draft leaves fewer workers, therefore the stats look better.

In contrast, the civilian economy feels a heavy strain, resulting in a nonstop rise in prices. Inflation stayed high in 2024, hit 9.6% in December, and is set to hover near 6.5%‑7% by late 2025; that’s because demand stays strong, defense workers get big pay, and the ruble likely weakens whenever oil prices move. The government’s put about $149 billion on the military in 2024, roughly 7.1% of GDP and 19% of total spending; therefore, the focus is seemingly clear.

Source: TradingView

The strategic success of parallel imports and quality sacrifice

One of the biggest things in Russia’s adaptation is its success at building massive parallel‑import networks to slip around export controls on hot‑wanted goods, especially tech that can be used both civilian and military. This is working: In 2023, Russia managed to import anywhere from 60% to 170% of the restricted items compared to pre-war levels in 2021. However, this success has a hidden cost. Russia has been forced to substitute high-quality Western goods with “lower-quality alternatives” supplied by countries like China, Turkey, and Kazakhstan. While sanctions have forced them to accept lower quality and higher shipping costs, they have largely failed to halt the supply of war materials.

Furthermore, key partners like India have become major transfer points for restricted technology, even helping to ship advanced U.S.-branded chips to Russia.

The shadow fleet

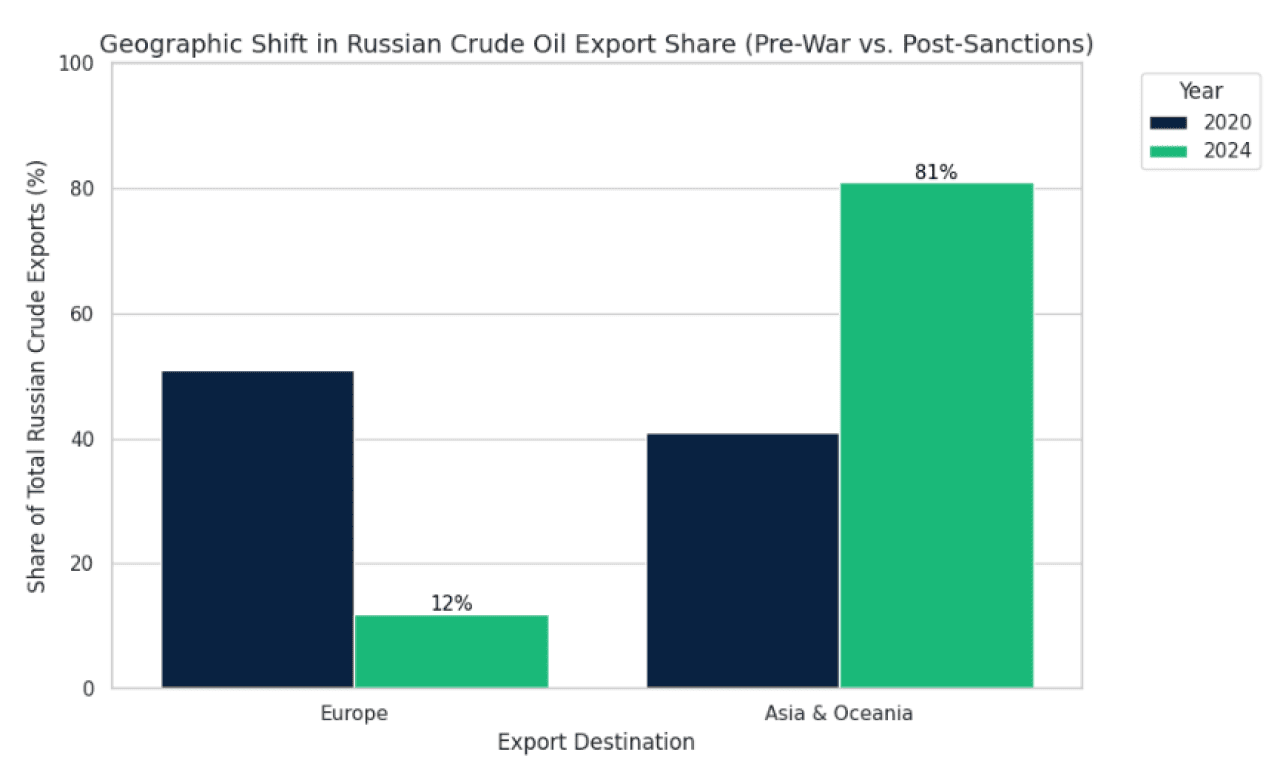

So, Russia sidestepped the G7 oil‑price cap by secretly amassing a massive fleet of tankers now called the shadow fleet. Since the 2022 sanctions, the shadow fleet has grown to over three times its original size.

This fleet is crucial for maintaining oil revenue, as it moves oil products without using regulated Western insurance and tracking systems. A major irony and flaw in the sanctions system is revealed here: Most of these shadow tankers were actually sold to Russia by Western companies, with Greek operators being the largest sellers.

This means Western businesses, motivated by the profits from selling off old, risky ships, equipped Russia with the exact tools it needed to evade the price cap. This situation highlights a serious regulatory loophole: relying only on financial bans (the price cap) without strictly controlling the sale of physical assets (the tankers). These old, poorly insured vessels also pose a high risk of causing a major environmental disaster in global waters.

The China-Russia relationship

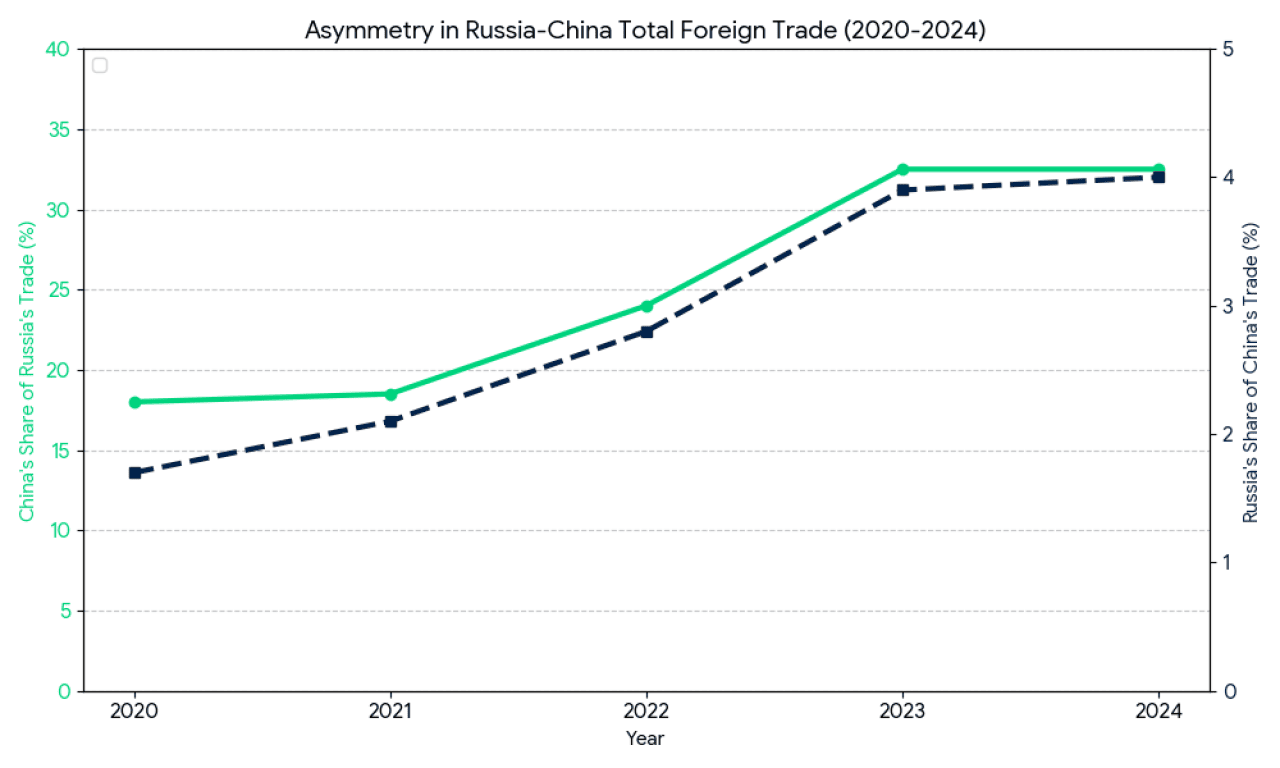

Since 2022, Russia has leaned on China like a rope; China ships factory goods and high‑tech gear while Russia gives oil and metals, so China’s spot as the biggest trade partner is the thread that keeps Russia standing.

The relationship, however, is structurally asymmetric. While trade with China represents 26% of Russia’s total trade, Russia accounts for only about 4% of China’s trade turnover. This inherent asymmetry grants Beijing considerable economic leverage over Moscow, although this leverage is often unspoken. Despite the strategic alignment, the reliance on China introduces a major vulnerability: the threat of U.S. secondary sanctions against Chinese financial institutions. The mere threat of such sanctions, outlined in a December 2023 U.S. executive order, resulted in a measurable slowdown in China-Russia trade during the first half of 2024, underscoring that the U.S. retains potent leverage through China’s deep integration into the dollar system.

Source: LSEG

A look at the sanctions quartet

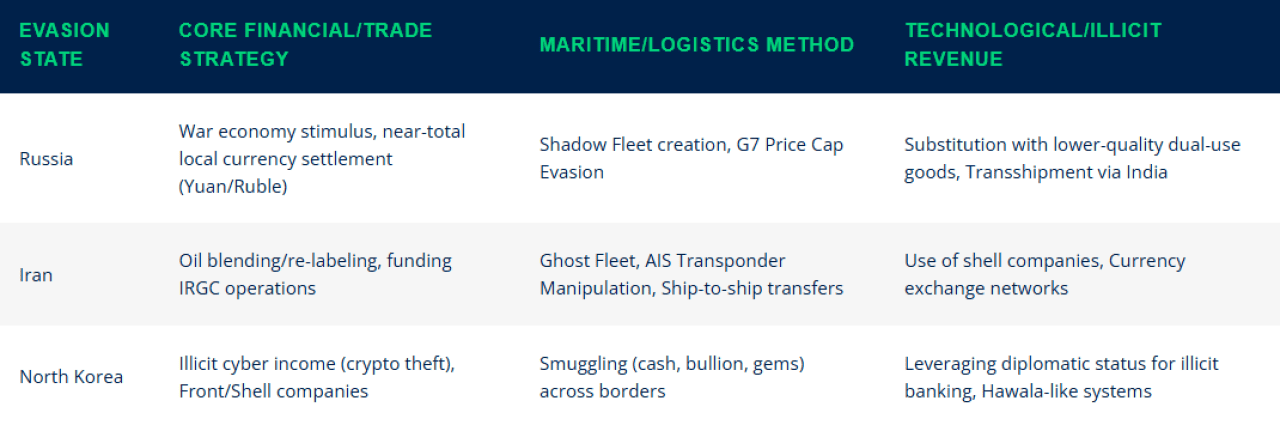

Russia’s circumvention strategy is built on the models of states that have long been isolated and have perfected the art of not only surviving under sanctions but also making large portions of their economies function relatively normally. Two of the most notable models for this kind of survival are Iran and North Korea.

The cooperation among these nations, sometimes referred to as the “Sanctions Quartet” (China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea), is creating a formal system of state-level resistance to the West’s financial power. China provides financial stability and market access, while Russia contributes resources and military technology.

Iran and North Korea: Advanced evasion prototypes

Iran’s playbook served as a guide for avoiding oil export bans. Following 2018 U.S. sanctions, Iran created its Ghost Fleet, pioneering techniques like using fake companies, registering ships under foreign flags to hide ownership, turning off tracking devices (AIS transponders), conducting risky ship-to-ship transfers, and blending oil to hide where it came from.

North Korea, as the world’s most isolated economy, perfected ways to move and create secret cash outside the regulated system. These methods include using diplomatic staff to set up illegal banking networks, moving cash between front companies using informal systems (like Hawala), and generating huge income through illegal digital activities like crypto theft and ransomware. North Korea’s focus on cybercrime highlights that the future of sanctions evasion is in sophisticated, high-volume digital finance that completely bypasses traditional bank monitoring. By combining Iran’s physical shipping tactics with North Korea’s digital cash-generation methods, Russia has created a highly resilient model. This confirms that when a country is cut off from systems like SWIFT, it is forced to turn to highly sophisticated, illicit digital activities to generate the untraceable money needed to fund its state operations and maintain liquidity.

The following matrix illustrates the institutionalized learning and hybrid strategy employed by these sanctioned states:

OANDA

De-dollarization as a geopolitical countermeasure

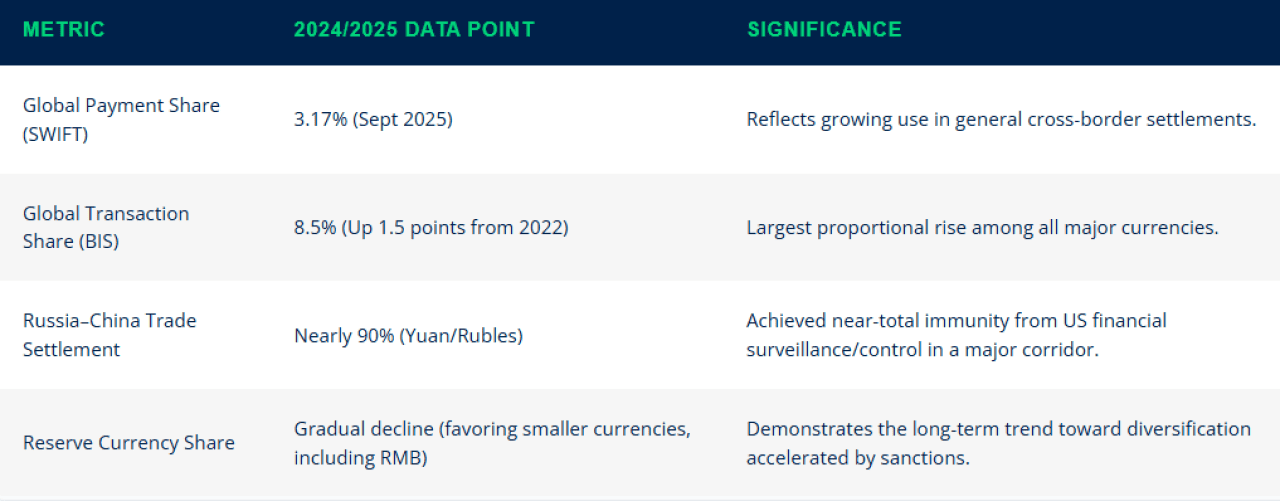

The move away from the U.S. dollar, known as de-dollarization, is happening for two reasons: political and economic. The main geopolitical reason is risk mitigation; after seeing Russia instantly cut off from the global financial system, emerging countries realize that financial independence relies on finding alternatives to the dollar and the SWIFT system. This political necessity is now aligned with new economic incentives, as interest rates have made borrowing in the Chinese yuan (RMB) cheaper than borrowing in U.S. dollars for the first time in nearly two decades. This gives private businesses a profit-driven reason to switch currencies, regardless of their political views.

The shift toward the yuan is growing quickly and can be measured. The yuan is now the world’s fifth-largest trading currency, driven by both economic changes and, importantly, by geopolitical pressure. The best example of this is the trade between Russia and China, where nearly 90% of transactions are now settled in yuan or rubles. This completely protects their largest trading relationship from U.S. dollar control. This change is also spreading to the commodity market, with Russian oil increasingly sold to countries like India in their local currencies, reducing the buyers’ need for U.S. dollar reserves. Even Saudi Arabia, a traditional U.S. ally, is considering using yuan-denominated futures for its oil pricing.

The overall effect is that the U.S. has achieved short-term political goals through sanctions but has simultaneously damaged the dollar’s long-term stability by speeding up the global trend toward currency diversification.

OANDA

The expansion of the BRICS group (now including major energy producers like Iran and the UAE) creates a powerful, unified bloc. This coalition is explicitly working to counter Western financial dominance by building alternatives to the dollar-based system, such as a decentralized payment mechanism called “BRICS Pay.” More than 50 countries have expressed interest in joining this initiative.

Furthermore, the planned technological link-up between China’s CIPS payment system and Russia’s SPFS system is laying the groundwork for a dedicated, non-U.S. dollar payment rail that can bypass Western financial controls entirely. This fragmentation of global finance is tied to changes in physical trade, as BRICS infrastructure investments are redirecting global trade routes toward south-south corridors, moving the center of economic power away from the U.S. and Europe. The sanctions provided the critical spark needed to ensure that the yuan is used in these new trade flows, which means Washington is losing control over both the physical movement of goods and the money used to pay for them.

The paradox of the US financial power

Are the risks of financial weaponization strategic fallout? The U.S.’ huge cash power feels like a paradox; therefore, it doesn’t always help its strategy. So, is America letting its own power fade?

The answer, according to experts, is yes. Critics argue the U.S. has “weaponized the dollar,” creating an unfriendly environment that pushes even its allies to look for alternatives to reduce their risk of being punished next.

High‑up U.S. officials see the risk, therefore, they say we have to avoid hasty one‑sided sanctions or the world will lose trust in how America runs its money, right? By continuously applying this strong financial pressure, the U.S. naturally weakens the key advantages, like reliability and political neutrality, that originally attracted the world’s money to the dollar system.

The unshakeable pillars of dollar dominance

Despite the measurable growth of the yuan and the push toward moving away from the dollar (de-dollarization), many financial experts agree that talk of the dollar’s immediate collapse is exaggerated. The dollar is protected by powerful, hard-to-change structural factors.

Consider the massive cash flow in U.S. markets, a court system you can trust, and dollars that turn into other money instantly; therefore, trying to operate worldwide without the dollar? Costly.

Historically, the strongest currency has always belonged to the strongest nation; as one expert stated, “currency power is a derivative of national power — guns count.” The U.S. military power and strong alliances (like NATO) provide the ultimate security for the dollar system, a level of trust that the Chinese yuan cannot match because of China’s lack of a fully independent political and legal system.

Furthermore, China’s own financial system is still deeply tied to the U.S.; its central bank holds about $1.4 trillion in U.S. assets. Crucially, the yuan is not freely convertible and lacks the legal stability required to achieve the massive liquidity needed to replace the dollar as the universal reserve currency.

Sanctions impact, systemic change, and conclusion

The sanctions deployed against Russia represent a double-edged strategic choice. Although they successfully hurt certain parts of the Russian economy, forcing the country to spend a huge 7.1% of its GDP on its military and causing high inflation for its citizens, they failed to completely stop the war effort.

Russia survived by successfully building strong ways to get around the sanctions, copying tactics from Iran and North Korea, and leaning heavily on China for economic support. Most importantly, these sanctions served as the clearest possible proof that countries need to avoid the USD system. This rapidly sped up the creation of new financial options and trade routes centered around the Chinese yuan. In the end, the U.S. gained short-term foreign policy victories but sacrificed some of its long-term financial stability and global trust.

The outcome is a major split in the global financial system: Instead of just the dollar leading everything, the world is shifting toward a multipolar system where the yuan increasingly handles low-risk trade in emerging markets, while the dollar remains dominant within the Western world.

This article is for general information purposes only. Opinions are the authors; not those of OANDA Corporation or any of its affiliates, subsidiaries, officers or directors.

This story was produced by OANDA and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.

![]()